Published - Thu, 21 Jul 2022

Chest Pain

Chest pain is not something to ignore. But you should be aware that there are numerous potential causes. It can feel like a slow pain or a sharp stab, among other things. It frequently has to do with the heart. Here are some types of Pain:

Visceral pain: Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves of the chest contain visceral afferent fibers. These non-myelinated fibers provide sensation from the heart, pericardium, lungs, and all visceral structures embryologically derived from the foregut.

Somatic pain: Sensation originates from the mesodermal structures through somatic innervation (e.g., the parietal pleura and peritoneum and muscular, skeletal, and dermal structures).

Referred pain: Since somatic structures in the spinal cord and brain stem receive synaptic projections from both visceral and somatic afferent fibres, somatic structures may experience visceral pain signals. As an illustration, consider how typical heart pain can radiate to the arms, neck, teeth, or jaw.

Chest pain that does not fall into any of the established categories is frequently referred to as "atypical" chest pain. It is best to avoid using this phrase to refer to "non-significant chest pain" since many serious diseases manifest in unusual ways.

Clinical features: The history is the most important tool in determining the cause of a patient’s pain.

Description of pain: It is necessary to get a description of the pain, including:

- Onset

- Location

- Degree

- Duration

- Radiation

The patient should be questioned about both aggravating and mitigating factors, such as activity, position, exercise, meals, respiration, and medications (especially analgesic and antacid use). Although not clearly defined, the distinction between visceral and somatic pain is clinically useful. On the other hand, disease processes in visceral organs can irritate nearby somatically innervated structures. For instance, a myocardial infarction (MI) can result in pericardial irritation, which causes the characteristic stabbing pain of pericarditis.

Description of previous episodes: It is important to look up any prior trauma or chest discomfort episodes.

Determination of risk factors: Many significant causes of chest pain have identifiable risk factors including

- The patient’s family history

- Medical history

- Social history (particularly on the use of cocaine, alcohol, or tobacco) may provide information relevant to the current episode.

Symptoms:

Symptoms of acute, critical illness includes

- Inability to speak

- Difficulty breathing

- Thready pulse

- Rapid or very slow heart rate

- Systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg

- Diaphoresis

- Confusion

Due to neurological connections in the brain stem and autonomic ganglia, autonomic symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, tachypnea, and eructation) are frequently linked to visceral chest pain., Coughing dizziness, fever, palpitations or weakness may be seen, depending on the underlying cause of the chest pain.

Differential diagnoses

Life-threatening causes of chest pain: Myocardial ischemia, Pulmonary embolism, Aortic dissection, Cardiac tamponade, Tension pneumothorax (Patients usually present with dyspnea accompanied by the signs or symptoms of shock and Acute esophageal perforation.

Serious but not immediately life-threatening causes of chest pain: Stable angina, Pneumothorax, Pneumonia, and Abdominal processes (diseases of the stomach, liver, gallbladder, spleen, and kidneys can cause chest pain by one of several mechanisms).

Chronic or benign causes of chest pain: Pericarditis, Mitral valve prolapse, Esophageal diseases (usually cause a poorly defined, burning, midsternal chest pain that can often be reproduced by asking the patient to swallow cold fluids or food), Musculoskeletal disorders, Pulmonary and abdominal processes of a less life-threatening nature (include viral pneumonitis, pleurisy, non-perforating peptic ulcer, biliary disease, chronic pancreatitis, and most forms of hepatitis).

Evaluation: A pulse oximeter, cardiac monitor, and blood pressure monitor should be used to monitor the majority of patients with chest discomfort until it is confirmed that they are not at risk for acute decompensation and do not require urgent care.

— Physical examination: As a part of the initial assessment of the ABCs, the vital signs should be noted before obtaining the history. All stable patients should have a thorough examination after paying initial attention to the cardiopulmonary assessment.

— Diagnostic tests: The electrocardiogram (ECG) gives direct and indirect information about many of the causes of chest pain. A chest radiograph, like electrocardiography, is a rapid, noninvasive, and inexpensive way of ruling out or identifying many of the diseases in the differential diagnosis (e.g., congestive heart failure, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and indirectly, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolus). An arterial blood gas (ABG) is rarely diagnostic but can be used as a measure of severity of illness or to assess acid-base status. Instantaneous information regarding a patient's oxygenation state is provided through pulse oximetry. Serum markers of myocardial injury (Cardiac troponins, Creatine kinase (CK), CK-MB subunit, and myoglobin) and Bedside echocardiography is diagnostic of cardiac tamponade and can provide information about cardiac wall motion and valvular function.

Disposition

— Admission: Patients with chest pain due to life-threatening causes require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and in some instances will require emergent cardiac catheterization or surgery. Patients with serious but not life-threatening causes of chest pain will most likely require admission to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment.

— Discharge: Patients with benign or chronic causes of chest pain can, in most instances, be safely discharged with a prescription for analgesics and arrangements for outpatient follow-up.

Created by

Comments (0)

Search

Popular categories

Latest blogs

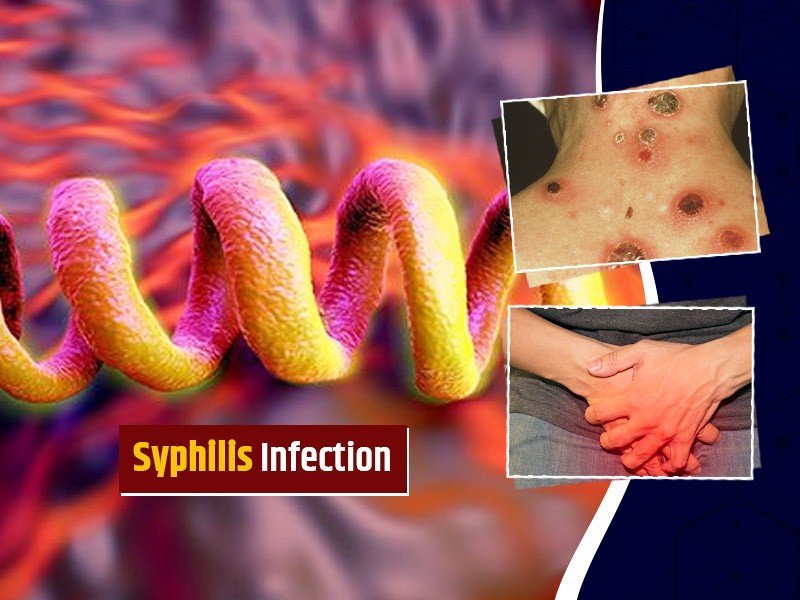

All you need to know about Syphilis

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

What is Pemphigus Vulgaris?

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

Know about Scorpion Stings

Sat, 12 Nov 2022

Write a public review