Published - Sat, 23 Jul 2022

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OF ABDOMINAL PAIN

Abdominal pain is the presenting complaint in approximately 5% of emergency department (ED) visits. Of these patients, 15% to 30% will have a condition requiring surgery.

—In patients complaining of abdominal pain, the most common discharge diagnosis is abdominal pain of unknown etiology (40% of patients).

—Gastroenteritis is the following most typical diagnosis (approximately 7 percent of patients).

—The following four most typical diagnoses for people with abdominal discomfort are appendicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, and ureteral calculi.

Evaluation:

1. Patient history

a) Characterization of the pain: Any change in the character of the pain over time should be noted because changes may give a clue regarding the organ involved. For example, appendicitis frequently starts as a vague cramping pain that worsens and localizes to the right lower quadrant.

i) Location

—Pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, myocardial infarction (MI), aortic aneurysms, and gastritis are all linked to epigastric pain.

—Right upper quadrant pain is consistent with hepatitis, large liver, gallstones, biliary colic, and cholecystitis.

—Patients with appendicitis, Crohn's disease, diverticulitis, or gynecologic conditions may experience right lower quadrant pain.

—Diverticulitis, ischemic colitis (which most frequently affects the splenic flexure), and gynaecological diseases are all linked to left lower quadrant pain.

ii) Quality

—A blockage of a hollow viscus, such as that caused by cholecystitis, a small bowel obstruction, or renal colic, is suggested by cramping pain.

—Burning pain is characteristic of gastro-esophageal reflux and peptic ulcer disease.

—Sharp, localized pain suggests peritoneal irritation.

iii) Radiation

—Left shoulder: Pain may radiate to the left shoulder in patients with a perforated peptic ulcer, sub-phrenic abscess, splenic rupture, or mononucleosis.

—Chest: Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a hiatal hernia, or peptic ulcer illness may experience chest pain.

—Back: Pancreatitis, abdominal aneurysms, and acute aortic dissection are the most common causes of back pain radiation. Gallbladder illness frequently causes right subscapular pain.

iv) Provocative and palliative factors

—Movement: Peritonitis patients experience agony with every movement.

—Position: Leaning forward can relieve discomfort for many pancreatitis patients.

—In cases of pancreatitis and cholecystitis, food may either make the pain worse or lessen it (as in peptic ulcer disease).

—Medications: The pain of gastritis, esophagitis, and peptic ulcer disease are typically relieved with antacids.

b) Associated symptoms:

i) Gastrointestinal symptoms

—Vomiting

- Bilious or feculent vomitus suggests a bowel obstruction.

- Indicators of peptic ulcer illness include "coffee grounds" or frank blood in the vomitus, a Mallory-Weiss rip, bleeding esophageal varices, gastric varices, or severe erosive esophagitis.

—The presence of anorexia and nausea is significant since it lowers the likelihood that appendicitis will be diagnosed.

—Diarrhea

- Bloody diarrhea suggests inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic bowel, and invasive gastroenteritis.

- Melena is consistent with an upper gastrointestinal source of bleeding and requires 150 mL or more blood loss.

—Severe constipation or obstipation suggests obstruction.

—As indicators of an infectious process, fever, sweats, and chills are present.

—Cancer, inflammatory bowel illness, and chronic ischemic bowel syndromes can all cause weight loss.

ii) It is important to take notice of any gynecologic or urologic symptoms as they may exclude gastrointestinal processes.

c) Past history

i) Surgical history: A bowel obstruction may be more suspect if there has been prior surgery.

ii) Medication history: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is associated with peptic ulcer disease. It is important to record any past use of steroids because they might conceal symptoms and make diagnosis considerably more challenging.

iii) Medical history: A medical history should be obtained, and any conditions that may cause discomfort should be questioned about (e.g., diabetes, sickle cell anemia, porphyria, peptic ulcer disease, hepatitis, gallbladder disease).

iv) Gynecologic history: It is necessary to obtain a gynecologic history, which includes finding out when the last period occurred.

v) Social factors

-Abuse of alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis, gastritis, hepatitis, and peptic ulcer disease.

-Smoking also raises the risk of developing pancreatitis and peptic ulcer disease. Strong vasoconstrictor nicotine slows recovery.

2. Physical examination

a) General appearance: While patients who are writhing in pain and prefer to move around should be suspected of having biliary or renal colic, patients who are lying extremely still may have peritonitis.

b) Head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat: Jaundice should be checked in the sclera and oropharynx since it can indicate biliary blockage or liver illness.

c) Chest:

i) Atrial fibrillation is typically the cause of an abnormally irregular heartbeat, which should raise the possibility of mesenteric ischemia.

ii) Since lower lobe pneumonia can induce abdominal pain, the lungs should always be checked for abnormal sounds.

iii) Men with liver disease may get gynecomastia as a result of low testosterone and increased estrogen effects.

d) Extremities: Examining the limbs for edema and palmar erythema, which point to liver dysfunction, is important.

e) Skin: Spider angiomata, which can develop in people with portal hypertension, should be checked for on the skin.

f) Abdomen: Repeat kidney, ureter, and bladder radiographs as well as ongoing abdominal exams can be important diagnostic tools.

g) Rectum: Rectal examination is crucial and may reveal a bulk or focused pain. Gross blood or occult must be observed. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is indicated by melena (black, tarry faeces with a distinctive odour).

h) Genitals:

i) To assess gastrointestinal disease in women and rule out a problem with the reproductive organs, a pelvic exam is required.

ii) To rule out epididymitis and torsion, which can cause referred abdominal discomfort in males, the genitalia should be inspected.

iii) To rule out an occult hernia in both men and women, the inguinal and femoral regions should be checked.

i) Back: Percussion of the back should disclose any costovertebral angle soreness, which could indicate nephrolithiasis or pyelonephritis.

Therapy: General supportive measures include the following:

1)The patient should be given intravenous access and given fluids as needed. Because the patient might require an endoscopy or surgery, nothing should be given orally to the patient.

2)Antiemetics (such as ondansetron, prochlorperazine), antispasmodics (such as dicyclomine, Hyoscyamine) antacids, or painkillers may be used in the pharmacologic therapy of symptoms.

Created by

Comments (0)

Search

Popular categories

Latest blogs

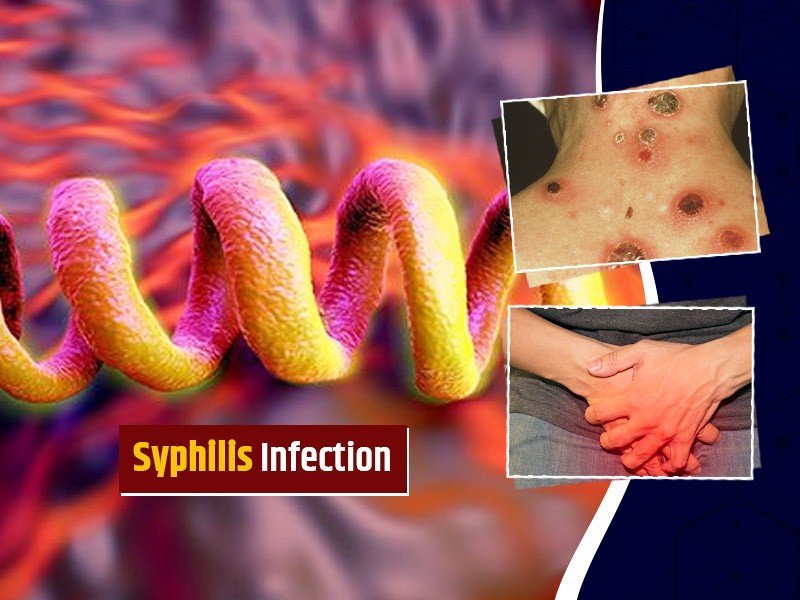

All you need to know about Syphilis

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

What is Pemphigus Vulgaris?

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

Know about Scorpion Stings

Sat, 12 Nov 2022

Write a public review