Published - Fri, 11 Nov 2022

Non-ketotic Hyperosmolar Coma

The syndrome is characterized by severe hyperglycemia, hyperosmolarity, and dehydration. Non-ketotic hyperosmolar coma is less common than diabetic ketoacidosis and commonly occurs as an early manifestation of non–insulin-dependent diabetes.

ETIOLOGY

1. Patients with diabetes who have been subjected to a stressor (e.g., infection, stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, pancreatitis) or who are taking thiazide diuretics, corticosteroids, phenytoin, cimetidine, propranolol, or calcium channel blockers may develop nonketotic hyperosmolar coma.

2. Non-diabetic patients: Situations that cause severe dehydration or excessive glucose load (e.g., burns, heat stroke, peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, and the ingestion of enormous amounts of sugar-containing foods) may cause this disorder in patients without diabetes.

PATHOGENESIS: Non-ketotic hyperosmolar coma and diabetic ketoacidosis represent different ends of a spectrum of lipid mobilization. Non-ketotic hyperosmolar coma is precipitated by stress that increases glucose levels over days or weeks. It is believed that a tiny dose of insulin will decrease ketogenesis. Osmotic diuresis that is significantly results in severe dehydration and altered mental status.

CLINICAL FEATURES

1. Patient history: Most patients are elderly with either non–insulin-dependent diabetes (67% of patients) or insulin-dependent diabetes (33% of patients).

2. Symptoms: Patients develop polydipsia and polyuria initially, followed by alterations in mental status. Before a stupor and coma set in, the illness can go undetected.

3. Physical examination findings: Dehydration, fever, hypotension, tachycardia, and a variety of breathing patterns are the main findings. Neurologic symptoms can include tremors, fasciculations, hemisensory abnormalities, and hemiparesis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES: Any disorder that can cause altered mental status (e.g., hepatic failure, uremia, sepsis, stroke, drug ingestion, lactic acidosis) must be considered.

EVALUATION

1. The values of measured and calculated serum osmolarity, glucose, and ketones are critical.

a) Usually, the glucose level is 1,000 mg/dL or above.

b) Although ketones may be present in small amounts, there is usually an absence of ketonemia and ketonuria.

c) Over 350 mOsm/kg or more describe the serum osmolarity.

2. Serum electrolyte, BUN, and creatinine levels; urinalysis; and venous blood gas determinations are indicated.

a) Serum sodium ranges from 120 to 160 mEq/L, and potassium depletion is usually severe.

b) Typically, the BUN is increased and the BUN:creatinine ratio is greater than 30:1.

3. Other studies: Finding the root of the problem is crucial. It may be necessary to perform a lumbar puncture, chest radiograph, ECG, computed tomography head scan, or cultures.

THERAPY

1. Fluid resuscitation: The average fluid deficit is 8 to 12 L; therefore, administration of half-normal saline (or normal saline for hypotensive patients) is indicated. The patient's hydration deficit should be filled in during the course of the first 12 hours, followed by the final 24 hours.

2. Replacement of potassium should begin early in the therapeutic process. If the patient's fluid status is such that he or she is able to produce urine, an infusion is typically started at a rate of 10 to 20 mEq/L for the first 24 to 36 hours.

3. Continuous infusion of insulin is used (0.1 U/kg/hour). As soon as the blood glucose level exceeds 300 mg/dL, the insulin should be stopped.

4. If the glucose level is under 250 mg/dL, glucose is indicated.

5. Phosphate: Administration of phosphate is controversial.

6. For the prevention of venous and arterial thrombosis, low-dose heparin may be administered.

DISPOSITION: A significant death rate is linked to non-ketotic hyperosmolar coma. Patients should be admitted to an intensive care unit because they are critically unwell. Transfer to other institutions is not recommended until the patient has stabilised and any other causes have been ruled out

Created by

Comments (0)

Search

Popular categories

Latest blogs

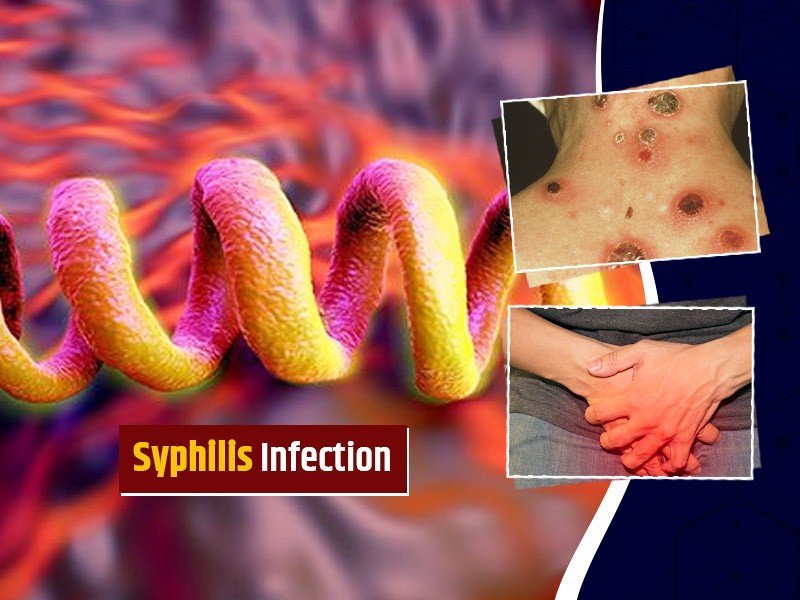

All you need to know about Syphilis

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

What is Pemphigus Vulgaris?

Tue, 15 Nov 2022

Know about Scorpion Stings

Sat, 12 Nov 2022

Write a public review